english

po polsku

po russky

english

po polsku

po russky

IMPROVISATION

KONTAKT

PRESSE

TEMPOGIUSTO

START

GEO INTERVIEW

UWE KLIEMT

ZITATE

IMPROVISATION

KONTAKT

PRESSE

TEMPOGIUSTO

START

GEO INTERVIEW

UWE KLIEMT

ZITATE

TERMINE

ANGEBOTE

TERMINE

ANGEBOTE

LINKS

INTERNATIONAL

LINKS

INTERNATIONAL

MEDIATHEK

MEDIATHEK

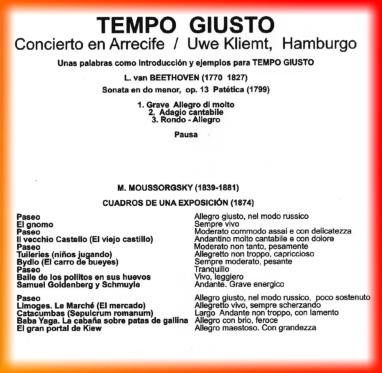

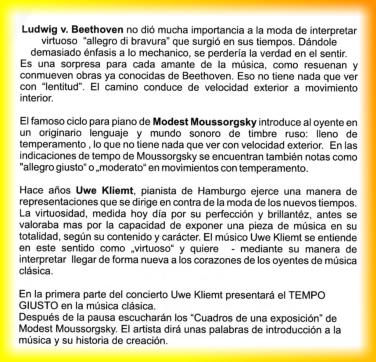

espagnol

espagnol

Uwe Kliemt, ur.1949, wykształcony pianista, ekspert CZASU, współzałożyciel Stowarzyszenia

Spowolnienia Czasu, oferuje szczególny koncept przeżywania muzyki klasycznej - koncerty wraz z bogato

towarzyszącymi im muzycznymi przykładami, moderacją słowną i przypowieściami dotyczącymi tempa w

muzyce otwierają każdemu miłośnikowi muzyki klasycznej nowe wrota przeżywania muzyki. „... nie-

słyszalne staje się słyszalnym... spowolniona gra pozwala na doskonałe wyłowienie subtelności

muzycznych...”,

„... spowolnienie nie oznacza wcale zamierania... balsam dla wszystkich zestresowanych uszu...” (z

różnorodnych gazet i reportaży).

Uwe Kliemt poświęca się od 1990 roku ciągle się nasilającej działalności koncertowo-wykładowczej w

sensie TEMPO-GIUSTO. Intensywne studia oraz kursy u W.R. TALSMY (Hiszpania), Dr Clemensa von

GLEICH (Holandia) i W.H. BERNSTEINA (Niemcy) otworzyły perspektywy nowej praktyce koncertowej.

Współorganizator Międzynarodowego Sympozjum TEMPA przy Wyższej Szkole Muzycznej w Amsterdamie

1995 r. oraz 23 Międzynarodowych Targów Wiedzy w zamku Michaelstein, działalność wykładowa

dotycząca „Tempa, rytmimi, metryczności i artykulacji”. Założyciel „Korespondenz TEMPO – GIUSTO” jak

również zainicjowanie różnorodnych seminaryjnych spotkań m.in.: Kongres TEMPO-GIUSTO w Japonii

1998 r. W ścicłym związku ze swoją nową orientacją muzyczną Uwe Kliemt poświęca się w coraz

większym stopniu pytaniu o orginalny obraz dźwięku i rozszerza swoją praktykę jako interpretator

klasycznej muzyki fortepianowej grając na oryginalnych instrumentach klawiszowych danej epoki. Jego

koncerty odbywają się regularnie w ramach inicjatywy „Muzeum dźwięków” w hamburskim Muzeum Kultury

i Sztuki gdzie pianista gra na oryginalnych instrumentach klawiszowych z bogatych zbiorów Dr A.

Beurmanna. Przyjaciel Polski i jak się okazało wielbiciel polskiej poezji i muzyki.

mailto:uk@tempogiusto.de

ТемпоДжусто

...в темпе, в темпе... сегодня это значит: торопись, это не терпит отлагательства!

Тоже слово раньше означало: подожди, пока представиться удобный случай

Слово «темп», которое в словаре Дудена 1700 года толковалось как «удобный случай», сегодня означает

«спешка», «поспешность», «гонка»

... отрывок из статьи одной газет города Гамбурга 1996 года:

«...в начале главный дирижер впопыхах ускорил темр коцерта Гайдна на несколько тактов. Так что молодому

пианисту пришлось отбарабанить свою сольную пратию со вспышками сфорцато и проявить беглость

пальцев.»

Такие сообщения сегодня не редкость. Тот факт, что темп музыкальных произведений в течение последний

двух столетий значительно повысился, очевиден и подтверждается многочисленными цитатами:

Вена (1807): «Стремление играть музыкальные произведения в ускоренном темпе берет вверх. Еще недавно

фортепианный концерт Моцарта исполняли в таком же темпе, в каком я его слышал в исполнении самого

Моцарта.»

Ганс-Иоахим Мозер (1950): «Особенно при исполнении динамичных произведений Моцарта мы, пожилые

люди, в годы нашей молодости стали свидетилями чего-то вроде переворота в стиле Коперника, когда Рихард

Штраус и прогрессивная молодежь его поколения «увеличили число оборотов» спокойных распевных мелодий

из Дона Хуана и Фигаро до такой степени, что получился совсем другой, как говорится, электрофицированный

Моцарт: бурлящий, сверкающий, захватывающий дух, потому что он сам стоял перед нами, едва переводя

дыхание.»

*

Как можно снова приблизиться к первоначальному темпу? И вообще возможно ли и надо ли стремиться

исполнять произведения так, как они звучали в подлиннике? Надо признаться, что мы никогда не сможем

воспринимать музыку так, как ее воспринимали современники Бетховена, так как наши уши привыкли совсем к

другому.

С другой стороны, возвращение к первоначальному (= сниженному) темпу дает возможность пережить

классическую музыку совершенно по-новому! Это очень актуально в наше время, когда мы во многих сферах

жизни «утратили способность слышать и видеть».

КОНЦЕРТЫ – ДОКЛАДЫ – СЕМИНАРЫ

Концерты Уве Клиемта, пианиста и «исследователя ВРЕМЕНИ» из города Гамбурга, относятся к

незабываемым музыкальным событиям. Исполнитель сам умело ведет концерты и объясняет в начале вечера

особенности своей интерпритации (ТЕМПО ДЖУСТО). Таким образом слушатели находятся в

непостредственном контакте с исполнителем и его музыкой, что придает концертам совершенно особый

характер. Музыкант Уве Клиемт сознательно исполняет музыкальные произведения не так, как это принято в

настоящее время. Так что даже такие известные произведения как Патетическая соната Бетховена звучат

совершенно по-новому. «Плачтично, красочно, захватывающе...» - так слушатели часто описывают свои

впечатления. Хотя Уве Клиемт и исполняет произведения в сниженном темпе, его манера исполнения не имеет

ничего общего с так называемой «заторможенностью»:

Живое внутреннее движение

приходит на смену механической скорости

Уве Клиемт - Kaudiekskamp 4a – 22395 Hamburg – Телефон 0049 40 / 604 69 76

Электронная почта: uk@tempogiusto.de

On reasonable tempi

The musical world will see itself concerned with the fact that a younger contemporary of L. v. Beethoven, - A.B. Marx,

musical director and cofounder of the Stern Conservatory in Berlin -, performed Beethoven's opus at half the speed than

we nowadays are accustomed to. "Technical practicability must indeed not mislead into a fast tempo; the first movements

of the sonatas op. 13, 28, 90, 101 could as well be performed as fast again as their contents presume."

The indication for the first movement of the Pathetique is even more precise and equals a tempo of 'Crotchets = 150' at

most. "it is probably not adequate to allow the tempo of the Grave and the Allegro to drift apart too much. The motion of

the Allegro should scarcely grow as four times as vivacious as that of the Gave, just in the way crotchets in the Allegro

are of less weight than one crotchet in the Grave."

The controversial proposition of Dutch musicologist W. R. Talsma on the metrical interpretation of classical instructions

for the metronome (back and forth as a unit! In the same way as the Roman passus was measured 1,48 m and meant

'right and left' and 7 days consist of 7 days and nights) is thus being verified by an independent third party.

Thus 'Minim = 144' has the meaning: crotchet forth, crotchet back, every single 'tick' a crotchet.

In other respects, almost all traditional instructions for the metronome dating from the early 19th century would have to be

performed in such a rapid manner which even nowadays is not being practiced. Should we believe in the music having

become slower? A rather absurd idea.

Intense studies of all partial aspects (and not only of the metronome instructions) have to be initiated now. From my

experience, these will be leading into rediscovering the forgotten classical musical culture.

In 1960 Fritz Rothschild already pointed out to the playing traditions having fallen into oblivion.

The sound of historic musical instruments very well suits this kind of interpretation. The transparency in sound and the

specific timbre of the Vienna 'Hammerflügel' being precise and at the same time chantlike, correspond to a kind of

musical idiom, thus conceding more significance to the single note.

In these terms, Beethoven lamented on tendencies, which even at that time could clearly be foreseen: "There lies a curse

on the virtuosos. Their practised fingers are always off in a hurry together with their emotion, sometimes even with their

mind".

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Sonata in C major KV 330

In a letter to his father, Mozart expressed his opinion on the manner of playing concerning Abbe Vogler (1778):

"... before dinner he played my concerto ... in a Prima Vista droning manner. The first movement went Prestissimo, the

Andante went allegro and the Rondeau indeed Prestißißimo... The audience could not judge than having seen music and

piano being played. They listen, think - and perceive as little - as he himself does. You can easily imagine the situation

went beyond endurance, since I could not suppress to communicate him, "much too swift". By the way, it is much easier

to perform a piece rapidly than slowly!... "

The first movement of the sonata features several passages containing demi-semi-quavers. This modifies the basic

motion of a piece since the tempo had to follow the fastest note values. Mozart could as well have demanded a 4/4 time

signature with semi-quavers. But a 2/4 time signature with "faster note values" requires a more gentle performance of the

piece. "Allegro moderato" all the more implies a moderate motion, since the allegro "certainly indicates a merry but not a

precipitate tempo" (Leopold Mozart: Violinschule).

The second movement "Andante" does not form a counterpart but leads to a well-balanced intermediate degree in

motion.

The last movement is marked "Allegretto", which - with reference to Leopold Mozart appears "slightly slower than allegro.

It usually implies something agreeable, pleasant and humorous and shares many aspects with the Andante(!) ". Following

this hint the triplet figures do not fall victim to a "virtuoso passage mania", but solemnly rise up to an animate and vivid

musical idiom. Music turns into "a song resembling closely to discourse".

Ludwig van Beethoven, Grande Sonate Pathétique op. 13

In the course of the first movement's tempo the habitual tremolo-vibration of the lower notes in the Allegro movement is

being transformed into a hurry-like motion of octaves, called drumming basses. An unsteady progressive motion lies

within this propulsion, on which large-scale chords are being accumulated in epic order. The second theme regains it's

"lamenting" expression (with reference to Carl Czemy). A clearly accentuated progression of quavers in a characteristic

staccato (Czemy) leads to a truly pathetical ending song and by means of expressive suspended dissonant chords into a

downward movement, which is kept in a piano mood at first. The question concerning tempi must be regarded as a

different one in the second movement. "The classical Adagios in general were not as slow as the romantic Adagios. The

metrical correlation between the parts within a beat, which form the entire beat, was kept intact,- in other words: the

classical Adagio was not 'stagnant." (Talsma)

Referring to Czemy, the last movement "Allegro" should be played vivacious, but not impetuous and with a "lamenting

expression". In this tempo the triplet figures turn into an expression of recital. The audience mill find itself in the position

of attentively witnessing a vivid dialogue emerging from both voices.

english

po polsku

po russky

english

po polsku

po russky

IMPROVISATION

KONTAKT

PRESSE

TEMPOGIUSTO

START

GEO INTERVIEW

UWE KLIEMT

ZITATE

IMPROVISATION

KONTAKT

PRESSE

TEMPOGIUSTO

START

GEO INTERVIEW

UWE KLIEMT

ZITATE

TERMINE

ANGEBOTE

TERMINE

ANGEBOTE

LINKS

INTERNATIONAL

LINKS

INTERNATIONAL

MEDIATHEK

MEDIATHEK

espagnol

espagnol